Still she haunts me, phantomwise, à la Lewis Carroll.

I figured something special might be happening that July morning in l948 when Mama appeared in the bedroom doorway, brandishing her boar-bristled hairbrush in one hand, my not-too-faded red plaid dress in the other.

“Skip the shorts and shirt today,” she said, handing me the dress. “Company˙s coming for lunch.”

“Who?” I asked, puzzled. I couldn’t think of anybody important enough to wear my Sunday dress for, but I slipped into it, and stood quietly while Mama tugged the brush through my snarls.

I had just turned 11. No longer in pigtails, I hadn˙t yet mastered pin curls. So I wore my hair shoulder length and loose around my face, with bangs that forever needed trimming.

Maybe I˙d learn to set it with bobby pins before I started junior high that fall. I waited for Mama to answer.

“It’s Nana,” she finally said. “Nana, and maybe Jean.”

I looked up sharply. Jean was my “real” mother, and I hadn˙t seen her for years.

I glanced across the bedroom at my older sister. Patti and I, just a year apart in age, had been adopted by our “real” father˙s sister and her husband in l942, when we were five and six.

Patti yawned, and then threw me a wink. Nearly a teen, she was more interested in boys than family gossip.

“Can I go over to Jimmy’s?”I asked, as Mama patted my bangs into place.

“Okay. I˙ll send Patti over to get you when they get here. Just don˙t get too dirty.”

Jimmy lived three doors down and was my best friend. The two of us would climb a towering maple tree to his roof where we would sit for hours, endlessly arguing. I favored the Brooklyn Dodgers and Doris Day. Jimmy loved the Giants and Peggy Lee. I liked Jack Benny, he Fred Allen. Though we rarely agreed, we relished our debates.

A few days earlier we had perched on the roof to watch the July 4 fireworks from the Los Angeles Coliseum. Some evenings we sat up there for hours with Jimmy˙s telescope, searching for UFOs. We even argued about the merits of the planets. I favored Jupiter, he Mars.

I˙d be glad to see Nana, Jean˙s mother, who always wore sweet gardenia perfume and talked about how she conferred with spirits at her spiritualist church. But I barely remembered Jean.

I knew my Daddy Al, of course, Mama˙s brother, because he visited from time to time. Jean, though, was just a shadowy background figure, referred to in disapproving whispers. She drank, I˙d heard. Or she had mental problems, whatever those might be.

She and Daddy Al had married when she was just a teenager, Mama said, and then Patti and I came quickly. Jean just couldn˙t manage. More important to me, I knew she was the daughter of a world-famous organist, Jesse Crawford, known throughout the 1930s as, “The Poet of the Organ.”

Grandpa Crawford sent Christmas cards with photos. I˙d heard that he˙d had radio shows in Chicago, and was the featured performer at Radio City Music Hall in New York City. My sister had inherited all that musical talent, but none trickled down to me.

“Jean could have been a concert pianist,” Mama said once.

Jean˙s brother, Howard, was a musician, too. My taste in music ran more to Vaughn Monroe, than classical. Ballerina was my current favorite that year. I˙d hum it all the time, but wished I could play it on the upright. Not fair, I used to think. I was the one with the middle name, Jean, so I should be the one with the family talent.

Jimmy and I argued well past noon until Patti eventually appeared.

“They˙re here,” she announced, with a smirk and a roll of her eyes.

I shinnied down the maple, careful not to tear my red plaid dress.

Jean looked younger than I expected, and prettier, with hair the same dark brown as mine, and freckles, just like mine, sprinkled across her nose. But during lunch she never smiled. Not once.

Nana talked of the seances she conducted. Mama talked of how Patti and I soon would be starting junior high.

Jean just sat, nibbled at her tuna sandwich, glanced about our tiny kitchen, and looked as bored as Patti. I wanted to ask if she had seen “Easter Parade,” my new favorite movie. I wanted to ask where she lived, if she traveled, if she liked to play Parcheesi or Tripoley. I wanted to ask if she remembered when I was born. Which did she like to read, Coronet or McCall˙s?

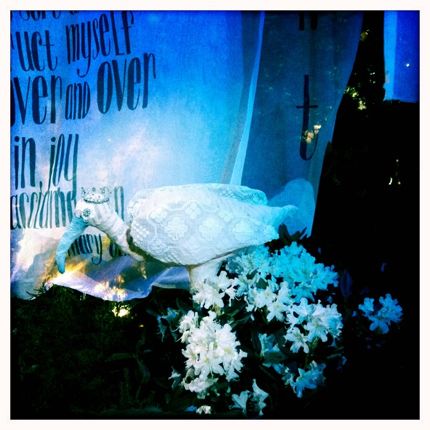

But soon everybody was saying goodbye. Jean gave Patti and me each a hesitant hug.

“You girls look great,” she said, the first words she˙d spoken directly to us all afternoon.

I wanted to tell her that I liked her freckles, but before I could speak, they were all piling into Nana˙s Studebaker.

Later that summer, Jimmy˙s family moved away and I never saw him again.

I, nor anybody else in our family, ever saw Jean again either. She just vanished. Nobody ever knew where she had gone.

One afternoon a couple of years after that visit, I heard on the radio that my Nana, Olga Crawford, first wife of famed organist Jesse, had died in an apartment fire at the age of 57. A few years later I sent for my birth certificate, which had been altered when I was adopted, to show Daddy and Mama as my parents.

Astonished, I found my middle name was spelled Jeanne, not Jean. Was this how my “real” mother spelled it?

Grandpa Jesse came to my high-school graduation and gave me a Smith Corona portable typewriter that I treasured all through college.

Throughout the late ’50˙s, I visited him frequently. He hadn˙t seen her since she was in her early teens and was uncertain about how her name was spelled.

I saw Daddy Al from time to time until he died in 1992. He had been married to Jean for such a brief time and so long ago. He had neither their wedding certificate nor divorce papers, so couldn˙t help me with the spelling.

Across the decades I think of her. Was she Jean or Jeanne? Did she read Hemingway or Fitzgerald? Would she choose pistachio or burgundy cherry if she were at Curries Ice Cream Parlor? Did she ever marry again or have more children? Did I have half-brothers or -sisters that I didn˙t know about?

Later, at UCLA, I spent a year interning for Los Angeles County Department of Adoptions while I worked on an MSW degree. I learned about the adoption rules of earlier days, about sealed birth certificates and efforts to protect birth mothers. I also learned why many adult adoptees feel an urge to know, a need for answers.

Even now, in my seventies, I˙d like to see my original birth certificate. Every time I sign my name, Theresa J. Elders, I wonder if that “J.” really stands for Jean or Jeanne?

And I still dream about climbing maple trees. . .and about my mother˙s freckles.

Editor’s Note: For more of Terri’s inspiring writing, visit her website: A Touch of Tarragon.