Inspiring Moment: Blue Heron

Written by Braiden

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: Crème Brûlée

Written by Braiden

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: Canada Geese Among Pilings

Written by Braiden

Comments and Praise

Grief: Five Common Myths

Written by Chelsea Hanson on September 26, 2011

Here are the five common myths of grief, as outlined by our talented new guest columnist, Chelsea Hanson.

Myth #1: Grief and mourning are the same experience.

Most people tend to use the words grief and mourning interchangeably. However, there is an important distinction between them. We have learned that people move toward healing not by just grieving, but through mourning.

Simply stated, grief is the internal thoughts and feelings we experience when someone we love dies. Mourning, on the other hand, is taking the internal experience of grief and expressing it outside ourselves.

In reality, many people in our culture grieve, but they do not mourn. Instead of being encouraged to express their grief outwardly, they are often greeted with messages such as “carry on,” “keep your chin up,” and “keep busy.” So, they end up grieving within themselves in isolation, instead of mourning outside of themselves in the presence of loving companions.

Myth #2: There is a predictable and orderly progression to the experience of grief.

Stage-like thinking about both dying and grief has been appealing to many people. Somehow the “stages of grief” have helped people make sense out of an experience that isn’t as orderly and predictable as we would like it to be. If only it were so simple!

The concept of “stages” was popularized in 1969 with the publication of Elizabeth Kubler-Ross‘ landmark text On Death and Dying. Kubler-Ross never intended for people to literally interpret her five “stages of dying.” However, many people have done just that, not only with the process of dying, but with the processes of bereavement, grief, and mourning as well.

One such consequence is when people around the grieving person believe that he or she should be in “stage 2″ or “stage 4″ by now. Nothing could be further from the truth.

Each person’s grief is uniquely his or her own. It is neither predictable nor orderly. Nor can its different dimensions be so easily categorized. We only get ourselves in trouble when we try to prescribe what the grief and mourning experiences of others should be-or when we try to fit our own grief into neat little boxes.

Myth #3: It is best to move away from grief and mourning instead of toward it.

Many grievers do not give themselves permission or receive permission from others to mourn. We live in a society that often encourages people to prematurely move away from their grief instead of toward it. Many people view grief as something to be overcome rather than experienced. The result is that many of us either grieve in isolation or attempt to run away from our grief.

People who continue to express their grief outwardly-to mourn-are often viewed as “weak,” “crazy” or “self-pitying.” The common message is “shape up and get on with your life.” Refusing to allow tears, suffering in silence, and “being strong,” are thought to be admirable behaviors. Many people in grief have internalized society’s message that mourning should be done quietly, quickly, and efficiently.

Such messages encourage the repression of the griever’s thoughts and feelings. The problem is that attempting to mask or move away from grief results in internal anxiety and confusion. With little, if any, social recognition of the normal pain of grief, people begin to think their thoughts and feelings are abnormal. “I think I’m going crazy,” they often tell me.

They’re not crazy, just grieving. And in order to heal they must move toward their grief through continued mourning, not away from it through repression and denial.

Myth #4: Tears expressing grief are only a sign of weakness.

Unfortunately, many people associate tears of grief with personal inadequacy and weakness. Crying on the part of the mourner often generates feelings of helplessness in friends, family, and caregivers.

Out of a wish to protect mourners from pain, friends and family may try to stop the tears. Comments such as, “Tears won’t bring him back” and “He wouldn’t want you to cry” discourage the expression of tears.

Yet crying is nature’s way of releasing internal tension in the body and allows the mourner to communicate a need to be comforted. Crying makes people feel better, emotionally and physically.

Tears are not a sign of weakness. In fact, crying is an indication of the griever’s willingness to do the “work of mourning.”

Myth #5: The goal is to “get over” your grief.

We have all heard people ask, “Are you over it yet?” To think that we as human beings “get over” grief is ridiculous! We never “get over” our grief but instead become reconciled to it.

We do not resolve or recover from our grief. These terms suggest a total return to “normalcy” and yet in my personal, as well as professional, experience, we are all forever changed by the experience of grief. For the mourner to assume that life will be exactly as it was prior to the death is unrealistic and potentially damaging. Those people who think the goal is to “resolve” grief become destructive to the healing process.

Mourners do, however, learn to reconcile their grief. We learn to integrate the new reality of moving forward in life without the physical presence of the person who has died. With reconciliation a renewed sense of energy and confidence, an ability to fully acknowledge the reality of the death, and the capacity to become re-involved with the activities of living. We also come to acknowledge that pain and grief are difficult-yet necessary-parts of life and living.

As the experience of reconciliation unfolds, we recognize that life will be different without the presence of the person who died. At first we realize this with our head, and later come to realize it with our heart.

We also realize that reconciliation is a process, not an event. The sense of loss does not completely disappear yet softens and the intense pangs of grief become less frequent.

Hope for a continued life emerges as we are able to make commitments to the future, realizing that the person who died will never be forgotten, yet knowing that one’s own life can and will move forward.

Article from Dr. Alan Wolfelt.

Please see the complete Grief Works library, which features over 50 articles from Dr. Wolfelt.

Copyright 2007, Center for Loss and Life Transition

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: Flowers in a Clear Cut

Written by Braiden

Comments and Praise

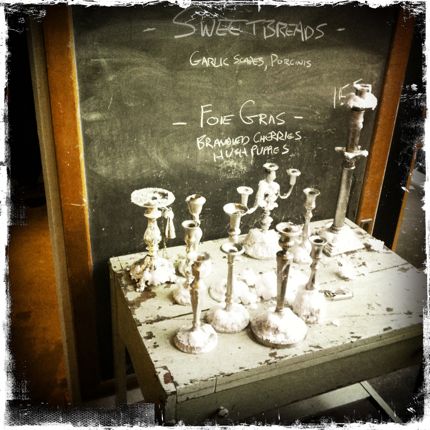

Inspiring Moment: Table Knickknacks

Written by Braiden

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: Fish Market Essentials

Written by Braiden

Comments and Praise

Heralding “The Help”

Written by John Paul Carter on September 22, 2011

Here’s another inspiring article from our monthly guest columnist, John Paul Carter, as originally published in his twice-a-month column, “Notes From the Journey,” in the Weatherford (Texas) Democrat.

William Barclay tells the story of a servant who was sent to meet a train on which his master’s friend, an English nobleman, was supposed to arrive.

The servant, who had never met the man, asked his master, “How will I recognize him?”

To which his master replied, “He will be a tall man helping somebody.” What a description!

I thought of that story after seeing the excellent film version of Kathryn Stockett’s best-selling novel, “The Help.” Set in Jackson, Mississippi, in 1962, the movie tells the story of three extraordinary women–Skeeter, a recent graduate of Ole Miss who aspires to be a writer–and two black maids, Aibileen and Minny.

Unlikely partners in a clandestine project to make public the working conditions of black maids in Southern households, their courage and determination forever changes a town and the way women – mothers, daughters, caregivers, and friends – view and relate to one another.

“The Help” exposes the blatantly cruel and unjust treatment of black caregivers by their prejudiced, white employers in a caste system based on race. At the same time, it graphically portrays a destructive human trait that is at the heart of slavery and racism but is as old as human history.

Wendell Berry describes it as “our inordinate desire to be superior – not to some inferior or subject people – but to our own condition. We wish to rise above the sweat and bother of taking care of anything – of ourselves, of each other, or of our country.”

As with the novel’s Hilley and her friends, there is in our society the pervasive belief that there are kinds of labor that are beneath us. It causes us to strive for a lifestyle that can afford to hire others to take care of the menial tasks, the dirty work, and the physical labor – often at less than a living wage. As a result, those who do such work are sometimes treated as second-class human beings.

In the movie, the tragedy went beyond what was happening to the black maids and extended to the relationship between their white employers and their children. Because the maids did almost all the caregiving for the children – changing, dressing, feeding, bathing, doctoring, playing, reading – the children became more bonded to the maids than to their own mothers. This diminished relationship between mother and child even continued into adulthood.

The lesson is clear that when we avoid the most basic kinds of labor, we weaken our essential relationships – with each other, ourselves, the earth, and our Maker.

It is the menial (from the Latin: “household”), repeated over and over, that binds us to each other.

Facing those same attitudes and practices in his day, Jesus identified himself as “the help.” He told his followers that he “came not to be served but to serve.”

And on the night when he was betrayed, Jesus not only shared the bread and cup with his disciples but also washed their feet.

By teaching and example, Jesus made it clear that to follow him is to join the ranks of “the help,” humbly serving each other and the world – not as second-class citizens but as his “friends.”

In our search for wholeness, the doctor of Lambarene, Albert Schweitzer, points the way: “I don’t know what your destiny will be, but one thing I know: the only ones among you who will be really happy are those who will have sought and found how to serve.”

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: Wildflower Forest

Written by Braiden

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: Radar Lab Going Out to Sea

Written by Braiden