Inspiring Moment: Three Geese at Green Lake

Written by Braiden Rex-Johnson

Comments and Praise

Are You REALLY Listening?

Written by Braiden Rex-Johnson on August 16, 2012

I do lots of reading on American Express’s Open Forum. It’s a great resource for everyone in business, but is especially meaningful and useful to a small business person, such as myself, who works out from home and doesn’t have the typical office interactions that those who work outside the home in corporate settings do.

This article by Stephen Shapiro, self-described “Chief Innovation Evangelist” and author of “Best Practices Are Stupid,” the #1 Innovation Book of 2011, really got my attention.

He recounts being on an airplane when things went wrong. Although fellow passengers (and he) didn’t really listen to the crew members’ instructions before the flight began, once there was an inkling of trouble just before landing, everyone aboard really started to listen.

Shapiro offers up several hints to listening better in What It Means to Really Listen:

The first step to listening better is to recognize the fact that you don’t. Ask yourself the following questions:

• Are you really hearing what others are saying? Or are you only passively listening?

• Are you focused on their words? Or are you thinking about what you will say next?

• Are you putting yourself in the shoes of the other person? Or are you only interested in meeting your own objectives?

• Do you ask a lot of questions? Or are you doing all of the talking?

• Are you hearing what they are really saying? Or are you too colored by your own perceptions, judgments and filters?

This last question is critical. If you are honest, you will most likely begin to see that your filters are getting in the way of communication. By recognizing that you even possess these filters, you can become more aware when they begin to color your interpretations. This allows you the choice to set them aside so you can create an effective opening to listen.

Are you really listening to those around you today? Do you register what your family and friends are saying, or just nod and go along with the status quo? Can you be a better listener, starting today?

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: At the Gym Collage

Written by Braiden Rex-Johnson

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: Bathroom Art

Written by Braiden Rex-Johnson

Comments and Praise

Five Years Without My Mother

Written by Braiden Rex-Johnson on August 13, 2012

Editor’s Note: This blog post first went up on August 13, 2010 in honor of the five-year anniversary of the passing of my mother, Julia Looper Rex. I am reposting it today since the words ring more clear than ever. Missing you today, and always, Mom!

I’m thinking about my beautiful mother today, exactly five years since her death.

This is a tough time of year for us, with our darling Bo-Bo’s death date on August 10 and Spencer’s mother’s death date yesterday. Interestingly and coincidentally enough, my mother and Spencer’s shared the same birth date. . .February 25. . .then died within a day of each other, although one year apart.

And my parents’ wedding-anniversary date falls next week. They were just short of 60 years of marriage when she died. . .

I have lots of Mom stories in my head that I want to share, and will write more about her as I am able. But today I want to share a life-changing experience I had almost a year to the day after she died.

In my vivid, oh-so-lifelike dream, Mom was propped up in her canopy bed in a pink nightgown looking regal, in just the way she always did.

She raised her hand and waved–queen-like–and I woke up.

I knew it was her way of passing over–or at least my brain’s way of putting me at ease–that she had moved on and was okay.

I have only rarely dreamed about her since. . .strange because the months following her death were especially sad and difficult ones for me to endure. . .and the dreams have been beautiful and most welcome.

Thanks, dearest Mom, for being the inspiration behind Five More Minutes With. We are thinking about and missing you today. . .

Comments and Praise

Darling Bo-Bo the Cat

Written by Braiden on August 10, 2012

Bo-Bo plays with the Christmas ornaments

Editor’s Note: This story originally ran on August 10, 2010, exactly six years after the death of our beloved feline of almost 16 years, Bo-Bo. I’m reposting it today in his honor. . .we still toast to him with every glass of wine. . .and his ashes still sit on our granite buffet in plain sight in our living/dining room. We love you, boy! R.I.P always.

I can still remember as if it were only yesterday the day I took Bo-Bo to the vet the final time. He hadn’t been eating well, his stomach was especially distended (he had always been a good eater, and more than a tad overweight as a result!), and he had stopped grooming himself (very uncharacteristic as he was part Siamese and a fastidious groomer).

After a brief exam, the vet came in, crouched down on her knees (I think to get more eye level with me) and told me he most likely had stomach cancer and to take him home and feed him Friskies or whatever he would eat until he died naturally or we thought we should put him down.

I was totally in shock, called Spencer (who offered to come pick me up in a cab, as he was worried about me driving home), yet I somehow made it home through the tears.

Once home, Bo took up residence in a white fluffy chair. I think, in their wisdom, that animals know long before we do that it is their “time.” I can tell you the “real” Bo-Bo, the one who came running to the door the minute he heard the elevator coming up the shaft, the one who butted you awake every morning at 6 a.m. so you’d grudgingly feed him, the one who stole butter off our butter plates every night at dinner, thinking we didn’t see him “sneaking” up on it. . .that animal left his physical body long before we did the inevitable.

It was a long (several-week) death march, and because I was here all day with him, I witnessed most every single moment of it. It was interesting that by the time I had determined that we had to let Bo go, Spencer still wanted to get tests, put him through chemo, etc. Some dear friends of ours had done that for their cat and they flat-out advised us NOT to undergo that. They reasoned that the extra days/week of life simply were not worth all the vet visits, and that toward the end they were afraid their cat hated them for putting him through it.

So when the inevitable day came, August 10 (my brother’s birthday, BTW–we reasoned that his good life would counter Bo’s sad death), we called a “mobile vet,” a very compassionate woman who goes around in her “vet mobile” making house calls. Bo hated going to the vet, and we couldn’t imagine him dying in that place of antiseptic smells and unfamiliar animals. We wanted him to die at home, in our arms.

The night before the day of Bo’s date with death, we both slept on the floor while he dozed above us on “his” chair. Of course, neither of us really slept. It was really a weird experience to know that this would be Bo’s last night on earth.

Just before 4 p.m., the vet showed up. The door was ajar; candles were burning; soft music was playing. Bo jumped down one last time for a bite of food, but could hardly make it to his bowl. I will always think it was an homage to me that his last moments on earth were spent eating. 🙂

Anyway, I held Bo on “his” chair through the whole process, from the initial sedation in the paw, to the actual injection of the fluid that stops the heart. And the whole way I talked him into his death, telling him it was all right, he was our boy, and he’d always be in our hearts. It was almost as if I were channeling another person, and Spencer said he’d never seen anything like it.

Bo-Bo died at 4:35 p.m.

To this day, I have no idea how I “knew” how to do that, or where that other “person” came from.

After he was gone, the vet left us alone and we arranged his body in his little cat carrier so she could take him away and have him cremated. Before she took the body, she made a plaster of paris molding of his little paw, and one of his hairs got stuck in it, and we will treasure that always.

A few days later, I had a vivid dream that Bo was at his food bowl. He turned to look at me as he walked away, and was gone. I KNOW it was his little spirit passing over, him letting me know he was okay, and that I/we’d be okay.

Our shrine to Bo-Bo

We put Bo’s ashes, the mold of his paw, and some other mementoes on our granite buffet along with a plant from my in-laws house (they are also gone) and Bo’s food bowl (a cute carved wooden cat that I planted with palms and a rubber plant) so we can “visit” him whenever we want. And every time we have a glass of wine, we toast to Bo by clinking twice instead of once. We both still think of him, and miss him, every day.

We haven’t gotten another animal and I doubt we ever will. When you’ve had the best, why mess around with cheap imitations? Once you’ve had that experience, why tempt fate?

Today marks the sixth anniversary of Bo’s death. And I am still missing him and loving him and writing this through the tears.

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: Red Dahlia at Green Lake

Written by Braiden Rex-Johnson

Comments and Praise

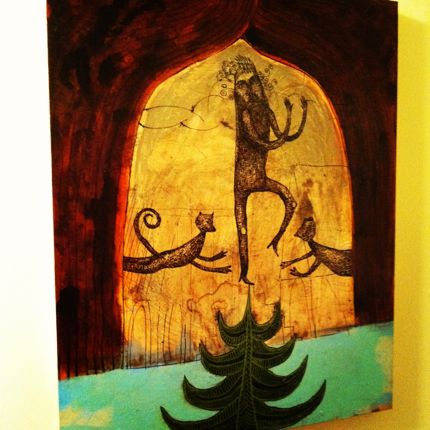

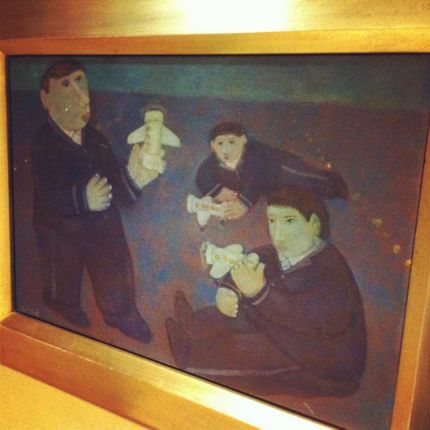

Inspiring Moment: Painting at Nordstrom Downtown Seattle

Written by Braiden Rex-Johnson

Comments and Praise

Inspiring Moment: Torchlight Parade Vendor

Written by Braiden Rex-Johnson

Comments and Praise

A Girl With An Apple

Written by Braiden Rex-Johnson on August 6, 2012

This came to me over the Internet and I just loved it. A true story of love and miracles!

According to the email:

A Girl With An Apple is a true story, and you can find out more by Googling Herman Rosenblat. He was Bar Mitzvahed at age 75)

August 1942. Piotrkow, Poland

The sky was gloomy that morning as we waited anxiously.

All the men, women and children of Piotrkow’s Jewish ghetto had been herded into a square.

Word had gotten around that we were being moved. My father had only recently died from typhus, which had run rampant through the crowded ghetto.

My greatest fear was that our family would be separated.

‘Whatever you do,’ Isidore, my eldest brother, whispered to me, ‘don’t tell them your age. Say you’re sixteen.

I was tall for a boy of 11, so I could pull it off. That way I might be deemed valuable as a worker.

An SS man approached me, boots clicking against the cobblestones. He looked me up and down, and then asked my age.

‘Sixteen,’ I said.

He directed me to the left, where my three brothers and other healthy young men already stood.

My mother was motioned to the right with the other women, children, sick and elderly people.

I whispered to Isidore, ‘Why?’

He didn’t answer.

I ran to Mama’s side and said I wanted to stay with her.

‘No, ‘she said sternly. ‘Get away. Don’t be a nuisance. Go with your brothers.’

She had never spoken so harshly before. But I understood: She was protecting me. She loved me so much that, just this once, she pretended not to. It was the last I ever saw of her.

My brothers and I were transported in a cattle car to Germany …

We arrived at the Buchenwald concentration camp one night later and were led into a crowded barrack. The next day, we were issued uniforms and identification numbers.

‘Don’t call me Herman anymore.’ I said to my brothers. ‘Call me 94983.’

I was put to work in the camp’s crematorium, loading the dead into a hand-cranked elevator.

I, too, felt dead. Hardened, I had become a number.

Soon, my brothers and I were sent to Schlieben, one of Buchenwald ‘s sub-camps near Berlin …

One morning I thought I heard my mother’s voice.

‘Son,’ she said softly but clearly, I am going to send you an angel.’

Then I woke up. Just a dream. A beautiful dream.

But in this place there could be no angels. There was only work.

And hunger. And fear.

A couple of days later, I was walking around the camp, around the barracks, near the barbed-wire fence where the guards could not easily see. I was alone.

On the other side of the fence, I spotted someone: a little girl with light, almost luminous curls. She was half-hidden behind a birch tree.

I glanced around to make sure no one saw me. I called to her softly in German. ‘Do you have something to eat?’

She didn’t understand.

I inched closer to the fence and repeated the question in Polish.

She stepped forward. I was thin and gaunt, with rags wrapped around my feet, but the girl looked unafraid. In her eyes, I saw life.

She pulled an apple from her woolen jacket and threw it over the fence.

I grabbed the fruit and, as I started to run away, I heard her say faintly,

‘I’ll see you tomorrow.’

I returned to the same spot by the fence at the same time every day.

She was always there with something for me to eat – a hunk of bread or, better yet, an apple.

We didn’t dare speak or linger. To be caught would mean death for us both.

I didn’t know anything about her, just a kind farm girl, except that she understood Polish. What was her name? Why was she risking her life for me?

Hope was in such short supply, and this girl on the other side of the fence gave me some, as nourishing in its way as the bread and apples.

Nearly seven months later, my brothers and I were crammed into a coal car and shipped to Theresienstadt camp in Czechoslovakia .

‘Don’t return,’ I told the girl that day. ‘We’re leaving.’

I turned toward the barracks and didn’t look back, didn’t even say good-bye to the little girl whose name I’d never learned, the girl with the apples.

We were in Theresienstadt for three months. The war was winding down and Allied forces were closing in, yet my fate seemed sealed.

On May 10, 1945, I was scheduled to die in the gas chamber at 10:00 AM.

In the quiet of dawn, I tried to prepare myself. So many times death seemed ready to claim me, but somehow I’d survived. Now, it was over.

I thought of my parents. At least, I thought, we will be reunited.

But at 8 A .M. there was a commotion. I heard shouts, and saw people running every which way through camp. I caught up with my brothers.

Russian troops had liberated the camp! The gates swung open.

Everyone was running, so I did too. Amazingly, all of my brothers had survived; I’m not sure how. But I knew that the girl with the apples had been the key to my survival.

In a place where evil seemed triumphant, one person’s goodness had saved my life, had given me hope in a place where there was none.

My mother had promised to send me an angel, and the angel had come.

Eventually I made my way to England where I was sponsored by a Jewish charity, put up in a hostel with other boys who had survived the Holocaust and trained in electronics.

Then I came to America, where my brother Sam had already moved.

I served in the U. S. Army during the Korean War, and returned to New York City after two years.

By August 1957 I’d opened my own electronics repair shop. I was starting to settle in.

One day, my friend Sid who I knew from England called me.

‘I’ve got a date. She’s got a Polish friend. Let’s double date.’

A blind date? Nah, that wasn’t for me.

But Sid kept pestering me, and a few days later we headed up to the Bronx to pick up his date and her friend Roma.

I had to admit, for a blind date this wasn’t so bad. Roma was a nurse at a Bronx hospital. She was kind and smart. Beautiful, too, with swirling brown curls and green, almond-shaped eyes that sparkled with life.

The four of us drove out to Coney Island . Roma was easy to talk to, easy to be with.

Turned out she was wary of blind dates too!

We were both just doing our friends a favor. We took a stroll on the boardwalk, enjoying the salty Atlantic breeze, and then had dinner by the shore. I couldn’t remember having a better time.

We piled back into Sid’s car, Roma and I sharing the backseat.

As European Jews who had survived the war, we were aware that much had been left unsaid between us.

She broached the subject, ‘Where were you,’ she asked softly, ‘during the war?’

‘The camps,’ I said. The terrible memories still vivid, the irreparable loss I had tried to forget. But you can never forget.

She nodded. ‘My family was hiding on a farm in Germany, not far from Berlin ,’ she told me. ‘My father knew a priest, and he got us Aryan papers.’

I imagined how she must have suffered too, fear, a constant companion.

And yet here we were both survivors, in a new world.

‘There was a camp next to the farm.’ Roma continued. ‘I saw a boy there and I would throw him apples every day.’

What an amazing coincidence that she had helped some other boy.

‘What did he look like? I asked.

‘He was tall, skinny, and hungry. I must have seen him every day for six months.’

My heart was racing. I couldn’t believe it. This couldn’t be.

‘Did he tell you one day not to come back because he was leaving Schlieben?’

Roma looked at me in amazement. ‘Yes!’

‘That was me!’

I was ready to burst with joy and awe, flooded with emotions.

I couldn’t believe it! My angel.

‘I’m not letting you go.’ I said to Roma. And in the back of the car on that blind date, I proposed to her. I didn’t want to wait.

‘You’re crazy!’ she said. But she invited me to meet her parents for Shabbat dinner the following week.

There was so much I looked forward to learning about Roma, but the most important things I always knew: her steadfastness, her goodness. For many months, in the worst of circumstances, she had come to the fence and given me hope.

Now that I’d found her again, I could never let her go.

That day, she said yes. And I kept my word. After nearly 50 years of marriage, two children and three grandchildren, I have never let her go.

Herman Rosenblat of Miami Beach, Florida

Editor’s Note: According to the email, “This story is being made into a movie called The Fence. This e-mail is intended to reach 40 million people world-wide. Join us and be a link in the memorial chain and help us distribute it around the world. Please send this e-mail to 10 people you know and ask them to continue the memorial chain. Please don’t just delete it. It will only take you a minute to pass this along. Thanks!